So when was the Copernican theory that the Earth revolves around the Sun first presented in the New World? This podcast presents a brand new discovery - that Copernican ideas may have been discussed at Harvard College as early as the 1640s under President Dunster. It turns out that Dunster owned a copy of the famous 1617 third edition of Copernicus's revolutionary book, De Revolutionibus. This third edition was titled, Astronomia Instaurata, or "A Restored Astronomy." It now seems very unlikely to think that Dunster did not at least discuss the Copernican theory with this first generation of Harvard students, even as he presented the Ptolemaic system to them.

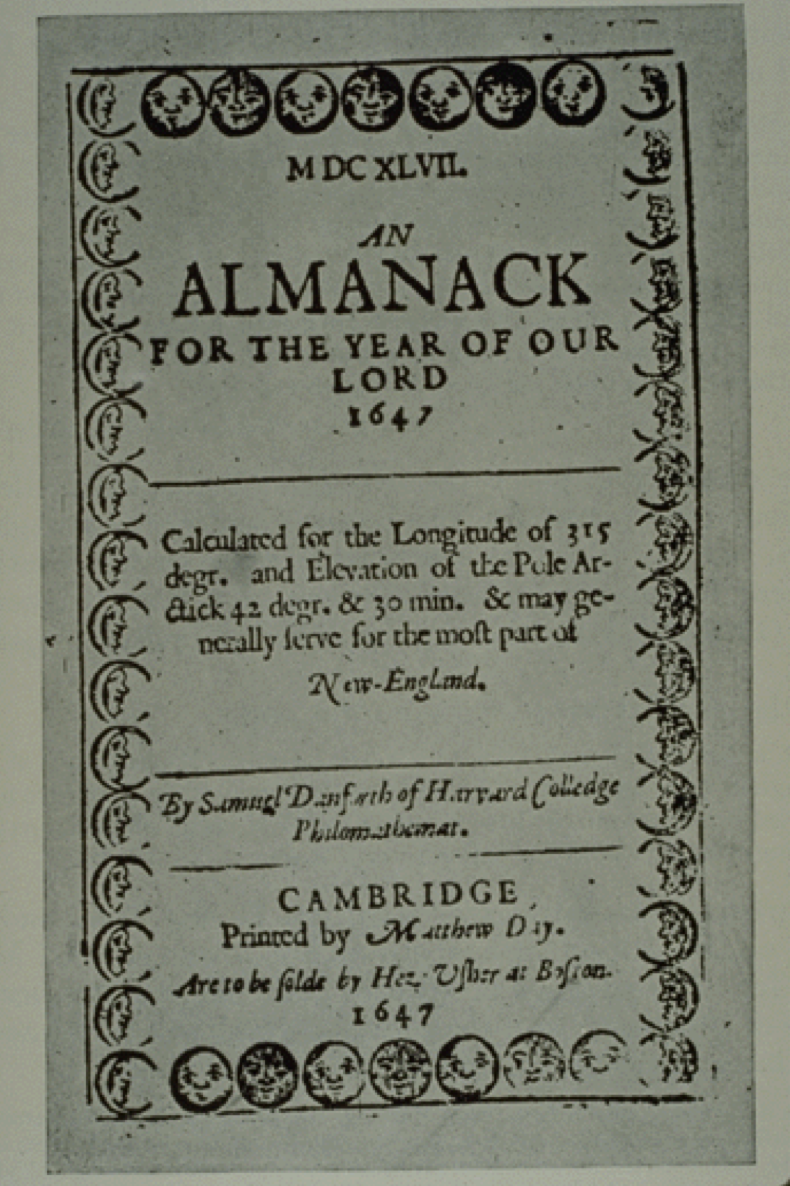

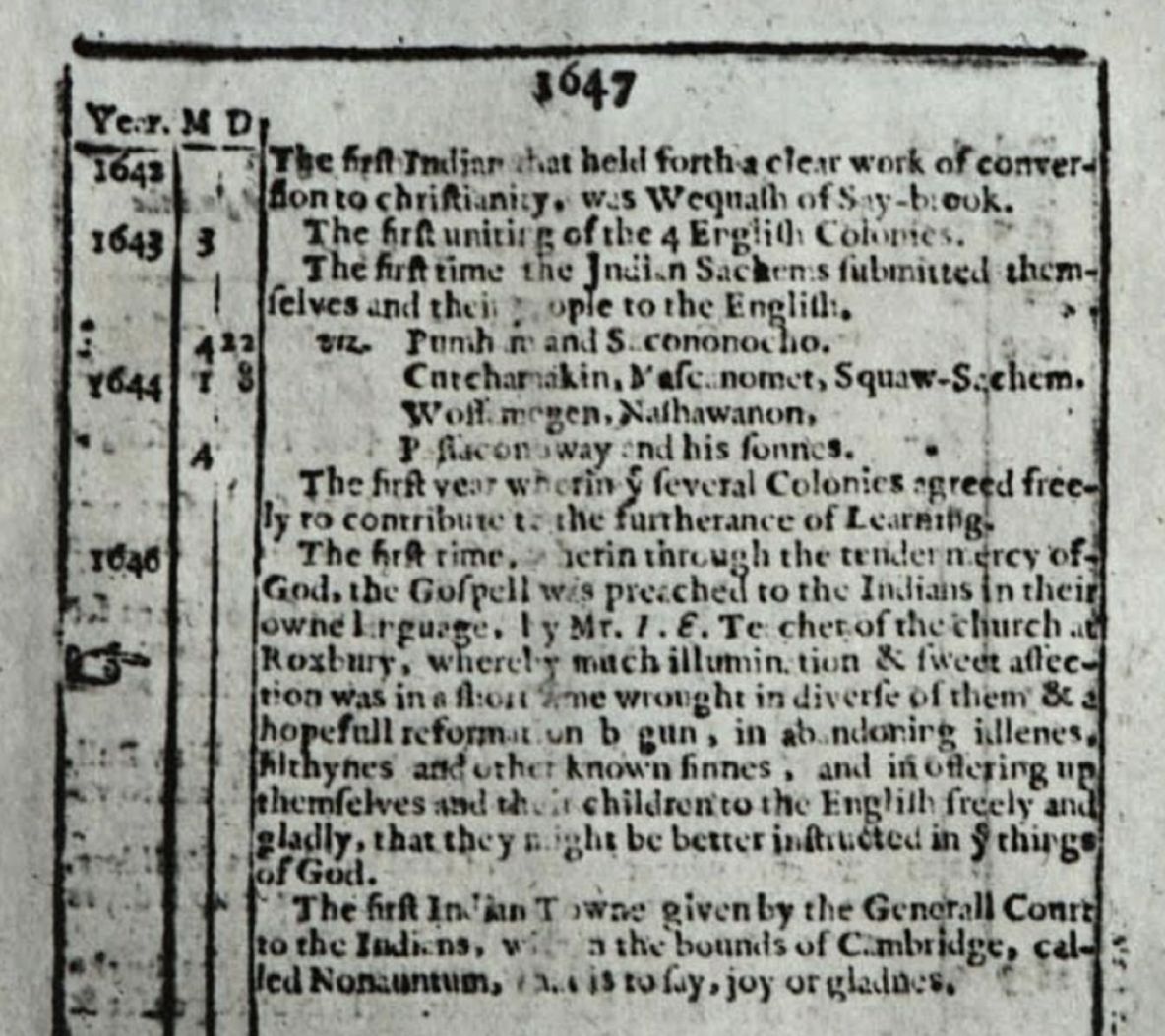

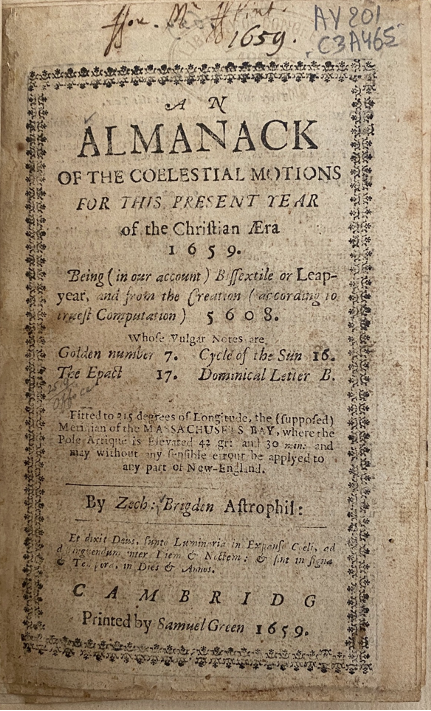

One of his students, Zechariah Brigden, went on after graduation to write a special pro-Copernican essay published in the Massachusetts Almanac of 1659. As famed Harvard historian Samuel Eliot Morison has noted, this essay was "the earliest extant scientific essay by a Harvard graduate.” Dunster's successor, Charles Chauncy, along with the governor of Connecticut at the time, John Wintrop, Jr., were so thrilled with Brigden's essay that they sent copies to one of the stalwart pillars of the Puritan establishment, John Davenport. How did Davenport respond, and what does this tell us about freedom of thought then in New England regarding one of the most revolutionary theories in history? How does it compare with leftist censors and institutions today who 'cancel' those with whom they disagree?